In 2021, I watched the comedian Varun Grover perform in New Delhi. As per usual, he had the audience in the palm of his hand. About 10 minutes in, Grover said (in Hindi), “Please understand the chronology. First, I tell the joke, then you laugh and finally, I go to jail.” The laughter was muted, not because people didn’t understand it, but because they understood it a little too well.

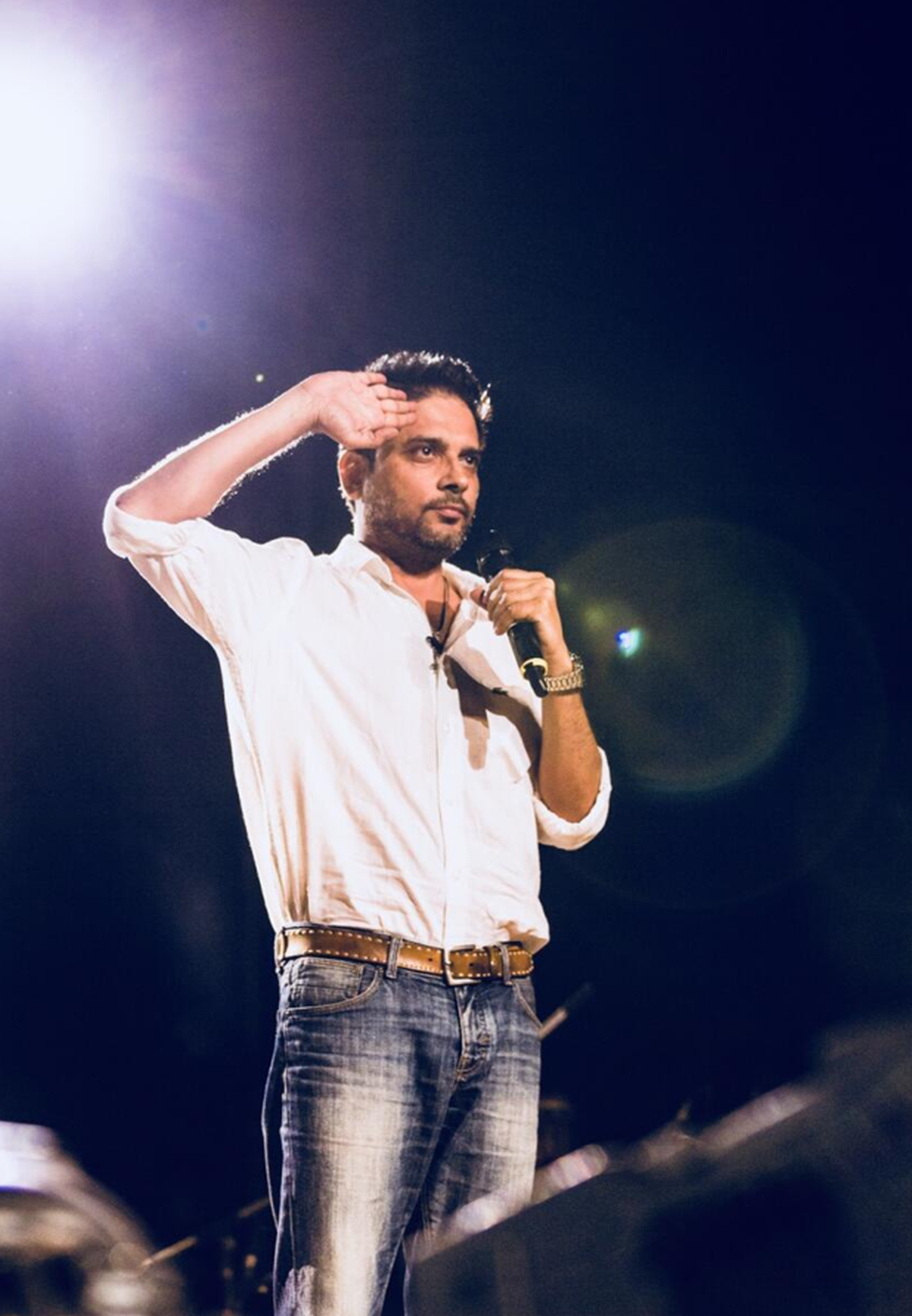

Varun Grover

The tension in the room was because back then, the comedian Munawar Faruqui’s legal troubles were hogging the headlines. Across January and February, he ended up spending over a month in jail for allegedly making offensive jokes about Hindu deities, a charge for which not a shred of evidence was ever produced.

Munawar Faruqui

Four years down the line it’s more of the same with Indian comedy. At the time of writing this column, Kunal Kamra had just been slapped with the second, third and fourth FIRs against him this week, after the comedian’s allegedly derogatory comments about Maharashtra Deputy CM Eknath Shinde, cabinet minister Nirmala Sitharaman, et al. The comments happened in the context of Kamra’s 45-minute stand-up special Naya Bharat on YouTube, which has received over 11 million views since it was released on March 23. Kamra’s Mumbai studio was also vandalised last week by supporters of Shinde’s faction of the Shiv Sena.

Kunal Kamra

Persecuting comedians

In India, comedy is still a fair way away from being a vehicle for social change. And one of the main reasons is that successive Indian governments — both at the state and central levels — have been trigger-happy when it comes to persecuting comedians. A decade ago, in 2015, All India Bakchod (AIB) uploaded a video where they, in conjunction with Bollywood celebrities such as Karan Johar, ‘roasted’ the actors Arjun Kapoor and Ranveer Singh.

The entire political ecosystem cried obscenity and multiple FIRs were filed against the comedians. AIB finally removed the video from their YouTube page. Since then, through the late 2010s and early 2020s, comedians such as Sanjay Rajoura have faced legal action on the flimsiest of charges. Like in 2016, when the actor and comedian Kiku Sharda was arrested after he did an impression of the religious leader and convicted rapist Gurmeet Ram Rahim, on the TV show Comedy Nights With Kapil.

Sanjay Rajoura

After Vir Das performed his Two Indias set at Washington D.C.’s Kennedy Centre in 2021, he faced a total of seven police complaints against him in various parts of the country — in Delhi, the complainant was a vice-president of the ruling Bharatiya Janta Party (named, sadly, Aditya Jha). Das also faced lawsuits for “objectionable material” after his Netflix TV series Hasmukh, about a small-town comedian who becomes a serial killer. Kamra himself has a previous contempt case against him in the Supreme Court, running since 2020.

Vir Das

Most recently, of course, comedian Samay Raina and podcaster Ranbeer Allahabadia (aka BeerBiceps) were the subjects of an FIR filed after allegedly objectionable jokes made during Raina’s paywalled YouTube series India’s Got Latent.

Personally, I see this largely as a cultural issue where the standards are very different for India vs. the rest of the world. We are an obedience-based culture focused on the needs of the collective, not a dissent-based culture where individual rights are paramount. And because of this, I don’t see individual outlier comedians affecting vital conversations in India anytime soon — the kind of conversations that lead to real change.

Samay Raina

System designed to reward compliance

Recently, I was watching the former English cricketer Steve Harmison answer a question about cultural differences between Asian and non-Asian cricketers. He replied that it was very tough for young players to be mavericks and rule-breakers in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh et al because they come through a system designed to reward compliance and punish dissent.

In my view, Harmison had hit upon something crucial to the discourse, and his point can be extrapolated to the comedic sphere as well. Why would a young, up-and-coming Indian stand-up comedian try to critique, say, caste and religion-based discrimination, or the gender wage gap, or any one of the zillion other problems in our society? If anything, they would be incentivised to swing to the other extreme, to cater to the bigotries and insecurities of the majority.

Can you imagine being a comedian who regularly performs in corporate events in India? Half the people hiring you want nothing else but jokes about their wives’ cooking, or jokes about how feminism “has gone too far”, or jokes about how you can’t catcall women anymore because of “woke culture”. The other half of your clientele consists of people who don’t actually want you to joke about anything at all. They want the comedic equivalent of white noise, words so anodyne and inoffensive that they kind of blend in with the ambience, like elevator music.

Which isn’t to say that actual change cannot be triggered by comedians. In America, basically the entire legal framework for mass-media censorship happened because of one legal case: FCC (Federal Communications Commission) vs. Pacifica Foundation, 1978, ending in a landmark 5-4 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld the right of the federal government to regulate content over the broadcast airwaves. The case itself only happened because of comedian George Carlin’s Seven dirty words monologue, wherein he listed certain swear words that could not be uttered on TV or radio, regardless of context.

Carlin was riffing off his predecessor Lenny Bruce’s monologue in 1966, where Bruce reeled off the words he had been arrested for in the past. A conservative activist filed the case against Radio Pacifica for airing the Carlin segment, which eventually brought about this outstanding ruling, rich in both legal and public policy arguments.

You may or may not agree with the U.S. Supreme Court’s judgment, but you cannot deny the rigour and the intellectual heft of the exercise. I would urge Indian comedians and politicians to read not only the judgment, but the arguments that preceded it. These are conversations we should be having right now, when the Internet has forever changed how the public consumes information and opinions.

Alas, we would rather file FIRs and vandalise studios than actually do the reading and construct informed arguments.

The writer and journalist is working on his first book of non-fiction.

Published – April 03, 2025 02:06 pm IST